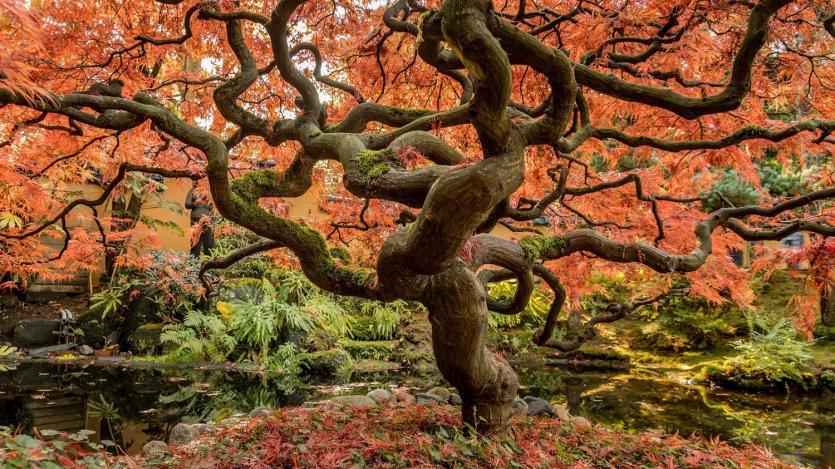

Japanese Maple. Photo by Faye Cornish on Unsplash

By Patryk Krych | The World Daily | FEBRUARY 1st 2022

According to a recent study by researchers who utilised codebreaking techniques originally devised during World War 2, there are currently an estimated 73,300 tree species on Earth – 14% more than have been discovered thus far.

The study used modern developments to techniques that had originally been devised to crack Nazi codes during World War 2, made possible back then thanks to the efforts of mathematician Alan Turing and his assistant Irving Good. Today, however, these methods could be used to help in conservation and environmental efforts.

The revelation of the existence of 14% more trees than was previously reported brings forth the implication that there are around 9,200 trees yet to be found and documented.

“It is a massive effort for the whole world to document our forests,” said a lead author of the paper, as well as a professor of quantitative forest ecology at Purdue University in Indiana, US, Jingjing Liang. “Counting the number of tree species worldwide is like a puzzle with pieces spreading all over the world. We solved it together as a team, each sharing our own piece.”

The research team had worked in 90 countries in order to achieve their results, collecting data and information on around 38 million trees. It was added that at least a third of all the undiscovered species of trees are rare, making them particularly susceptible to the changing climate.

Trees and forests are extremely important to the continuation of not just human life, but of the world. They’re responsible for the cleaning of the air, the control of erosion and flooding, as well as the filtration of water. As well as this, they’re also a precious resource that has been lowering in number over the years, especially since the increased rate of forest fires recently.

“These results highlight the vulnerability of global forest biodiversity to anthropogenic changes, particularly land use and climate, because the survival of rare taxa is disproportionately threatened by these pressures,” said one of two senior authors of the paper and University of Michigan forest ecologist, Peter Reich.